21st C “stained-glass” innovation

This is an account of innovative “stained-glass” work done by youngsters in a Sunday School in the first decade of the 21st Century. Designed for their parish church, it deploys plastics technology and was undertaken partly in reparation of mid-20th Century arson damage to its Victorian glass. I love this body of work because it shows great respect for the medieval. It is at once muscular, naive, and feeling: I risk saying that it leaps across centuries, just as great Old Stained Glass does.

St Mary’s church Woodford (High Street, South Woodford, London E18 2PA) suffered an arson attack in 1969. The church was mainly early 19th century, with galleries. (See below for an 1876 account of the building.) It had a big gothic stained glass window at the east end, over the altar. When the interior was rebuilt after the fire in the early 1970s, it was decided to put the altar at the west end. A new main door was put into the east end with a room for social events, committee meetings and so on. It was lit by the existing Victorian east window which was re-glazed with clear panes. None of the church’s stained glass in any part of the church survived the fire and the 1970s repair and rebuilding saw clear glass being put into the east end’s tracery window. In 2004 the window was chosen for an innovative “stained glass” project by a parishioner, the artist and teacher, Peter Webb.

Pete Webb takes up the story:

“I wanted the youngsters of the ‘Seekers’ group of 11-14 year-olds to produce a set of mock stained-glass windows which could be installed temporarily at will. I had heard of the use of acetate plastic sheet and special paints to make works of art which were light, flexible, strong, and translucent. It was important that it could be installed and dismantled at will: it was, if need be, a temporary piece of work.

“We began with the main window. Under my guidance, and that of a regular Sunday School teacher, the children chose the subject for the window, drew its elements, and composed the whole to actual size.

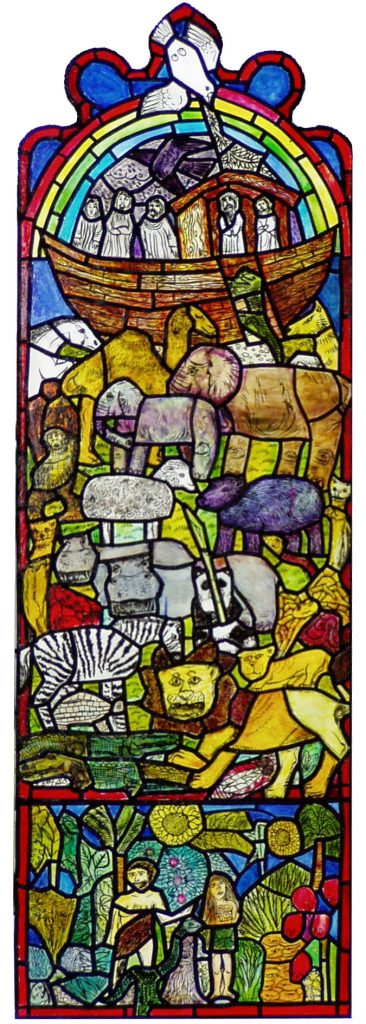

“Every child involved was guaranteed a creative role in the project. The group unanimously nominated Noah’s Ark as the subject for the big first window. The children were set to researching animals, boats, rainbows and human figures, which were then drawn roughly to the actual size required, cut out and collaged onto a piece of paper the same size as the window; black lines were added to represent leading, and the whole paper design was painted. It was then placed under the acetate, which had been cut to fit exactly the window embrasure, and the outlines were traced onto the acetate using removable black felt tip pen. Black sugar paper, representing the leading, was cut into strips, which were then bent or left straight and glued onto the acetate window with PVA. When all was dry, the areas of colour were painted onto the acetate, in more or fewer layers according to the density and brightness required. Detail was carefully painted in with thin black or dark brown line over the coloured areas. The window, when finished, was carefully wedged into its stone tracery frame, care being taken that it could not easily be dislodged.

“That first window – “Noah’s Ark” – was a little less than six feet high by eighteen inches wide. We designed the window on paper and then transferred the drawing to one-eighth inch clear acetate. We glued on black paper “leading”, and painted the images in the acetate-ready “glass” paint. The work was done during regular Sunday School sessions, with some extra time at my house or at the church as necessary. Several weeks were needed to do the job.

“The young makers of the window were introduced to pictures of medieval stained glass from English and French cathedrals, and to the roles – both structural and artistic – of leading in the originals. Our design method was very similar to that used for real stained glass in the middle ages.

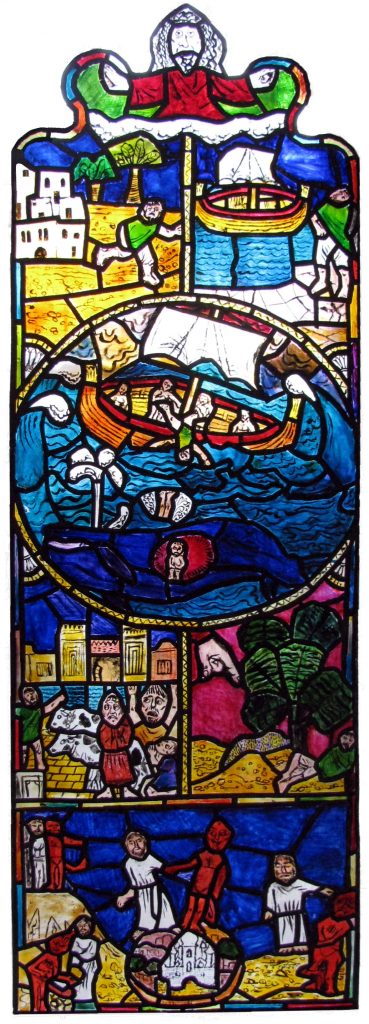

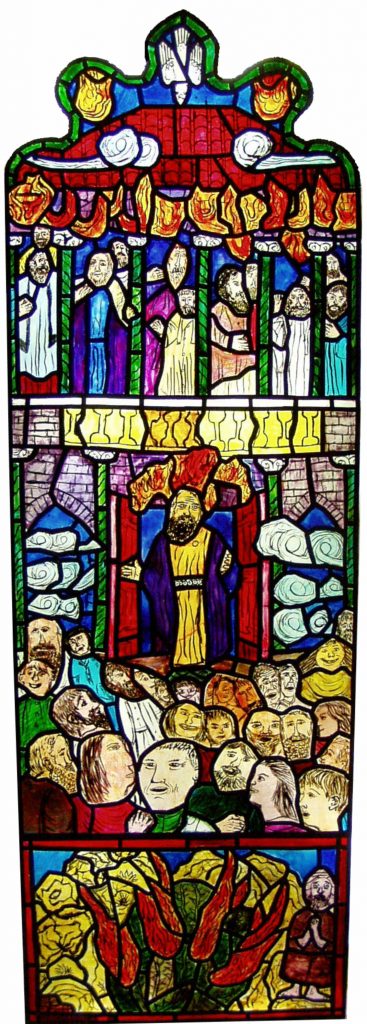

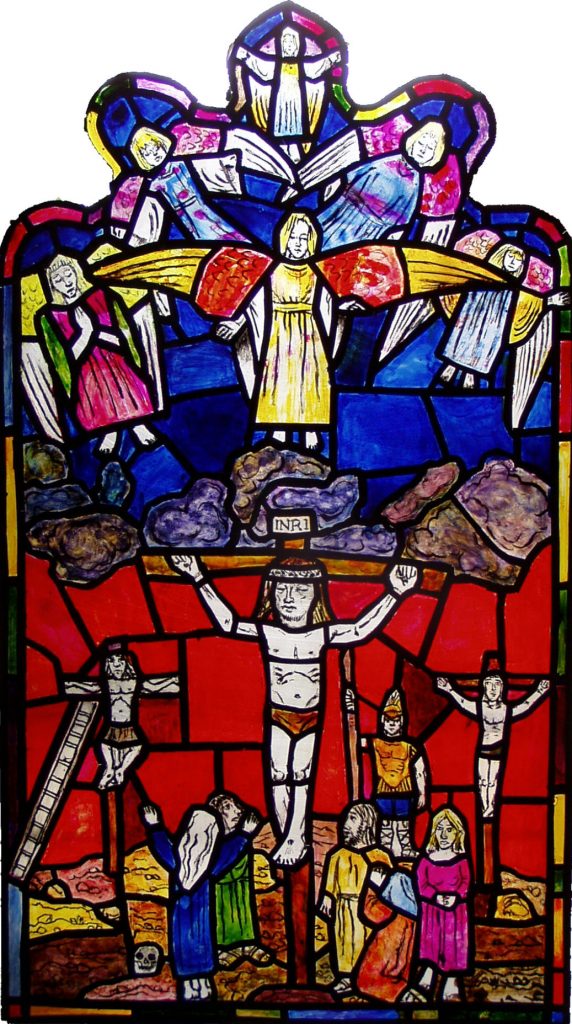

“We later produced painted acetate images for adjacent tracery spaces, the same size as the Noah window. These depicted the Pentecost and the story of Jonah. Finally, the group made a rather smaller Crucifixion window and finished the project in 2007.

“The Seekers all seemed to enjoy the process, and many declared themselves thrilled with the result.”

Notes by RDN

Note by #1

Ironies in church decoration

Pete Webb is not at all sure the Seekers’ work has survived and thinks St Mary’s congregation includes Anglicans who are rather iconoclastic in their views on church decoration

A couple of ironies attach themselves to the St Mary’s acetate project.

Inside the church, there is a memorial to the church’s vicars. For four years during Henry VIII’s reign, St Mary’s had the Rev John Larke as curate. His mentor Sir Thomas More in 1530 appointed Larke to be vicar of his own patch, Chelsea. Larke become one of the Blessed Martyrs of the Roman Catholic Church, being executed in 1544 (following More’s execution in 1535). Presumably Larke would have been rather sympathetic toward the new windows..

Outside St Mary’s there is a memorial to William Morris senior, in effect the grandfather of the Arts and Crafts movement, and a leader in the medieval revival, of both of which Webb is a devoted fan.

Note #2

The 2004-7 “Seekers” might please James Thorne, FSA (1815-1881)

John Thorne’s Handbook to the Environs of London, 1876, is scathing about the architecture and decoration of St Mary’s, Woodford, as it stood then. This popular antiquarian’s account underpinned Historic England’s entry for the church as a Grade II listed building.

Thorne’s Volume II’s various “Woodford” entries included:

“Woodford End consists of little more than a dozen commonplace houses by the ch., with a few great houses standing apart in elm-bordered grounds. Many new houses have, however, been built lately within the ch. District, but to the W. of the High Road. The church, St Mary, is very poor specimen of the Gothic of 1817. It is of brick covered with stucco, and consists of nave, aisles, and short chancel, S. porch, and tall battlemented W tower. The interior has galleries and pews, a wretched painted glass E. window, and is nearly as ugly, though not quite as mean, as the exterior….. South of the ch. is a yew tree, the trunk of which is over 14 ft. in girth at 3 ft from the ground.”

Leave a comment