Kate Hepburn, designer, 1947-2024

I want to honour the life of Kate Hepburn, the graphics designer, who died in Hampstead’s Royal Free Hospital in late July this summer. She made a big impression at Vole magazine in the late 1970s, and in many other creative ventures. Corrections and new information would be very welcome.

Kate Hepburn’s designs from 50-odd years ago remain striking. They reflected her personality which even on small acquaintance seemed to me confident but disarming, amused but serious, politically engaged but not adamantine. She left a strong impression and it is reinforced by all I have learned from her family (see the Camden New Journal Kate Hepburn obituary) or discovered online.

Kate Hepburn was a creative visual force for various striking ventures. First, in maybe 1969, when she was fresh out of the Central School of Art, and still studying at the Royal College of Art, came work with Terry Gilliam on his animations. Then, she in effect branded Monty Python’s forays into print with distinctive games in text and print, starting with their 1971 Big Red Book. Geoffrey Strachan, the Python’s publisher at Methuen, has commented that with their second book, The Brand New Monty Python Bok, “[Kate] was on her own and her own design/typographical genius took over and produced a masterpiece”. (Much of that story is featured in the Eye Magazine‘s Issue 54, “Understanding Silly Magazines”.) Soon, there were magazines, in 1972-3 with the founding issues of Spare Rib, the leading feminist magazine, followed by Vole, Richard Boston‘s literate environmental magazine from 1977 to 1980, and from 1979 Quarto, the short-lived literary journal edited by Richard Boston and John Ryle.

In the 1980s Kate went on to produce branding for the Muppets, the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd and several others. In this period Kate collaborated with the legendary AA-trained designer Mark Fisher on stadium sets for bands, and not least riffed on Hokusai’s “Wave” for the design-conscious Nick Mason’s painted drum kit. At some point (I haven’t pinned down the dates) she produced quite formal abstract prints, which – like her stage images – were worlds away from books and magazines.

From the age of 13, she was at the Camden School for Girls, a place famous for its feminism. She recalled the RCA as having rather testing sexual politics, as well as being creatively energising. She seems from the start to have held her own in starry – often male – company. She was with Derek Birdsall’s studio for the Python collaboration and with Wolff Olins for her work in rock ‘n’ roll and entertainment branding. She was more than feminist enough to appreciate working with women, and cited several as important to her, not least Sally Doust from Spare Rib days, and Nina Kidron, a colleague when she helped with the design side of Pluto Books, the forthrightly anti-capitalist publisher which did always contrive an almost perky visual appeal.

I only met Kate fleetingly and when my occasional visits to the Vole offices coincided with hers. This was in the Nash terraces of Park Square East, where she worked with Walter Junge, who was the in-house production manager. From the start, she produced many of the magazine’s covers, which proclaimed it as witty and composed. (My own favourite featured my then-hero, Ivan Illich and the critique of him offered by another hero, the Economist‘s Norman Macrae.) She was impressive without giving any sign of wanting or needing to be. She was smiling and friendly, but appeared quite capable of firmness.

In 1978, Kate and Walter Junge had a child, Usha Junge Hepburn, who grew up to be a Red Cross worker in her father’s Latin America. She is now hoping to produce a website devoted to her mother’s work. It will doubtless speak of Kate’s sister, Alison Telfer, who for many years was married to the Python’s Terry Jones (and makes yet another link between Kate and the world of the Pythons, whose offices were in a matching terrace diametrically across Regent’s Park from Vole). Terry was the main – perhaps the only – funder of Vole, so he was bound to hope Kate might help his fledgling production. Both Vole and Spare Rib needed to prove they had a relatable touch in their ardour, and Kate’s approach delivered it.

Alison and Kate’s mother, Margaret Hepburn, was an extraordinary person, born in colonial India, brought up in arty Hampstead, a code-breaker in wartime Bletchley Park, a founder of the Camden branch of Age UK branch, and devoted elderly swimmer in Hampstead Ponds. It is not the least of Kate Hepburn’s accomplishments to have taken up her late mother’s Age UK role.

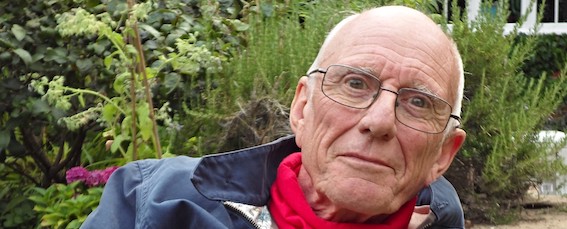

I am very tempted to think of Kate Hepburn as having the kind of easy unassertive confidence that the better kind of bohemian inheritance sometimes bestows. I have felt a lifelong resistance to Hampstead liberalism, which can be horribly superior and smug. But I remember knowing and admiring one or two Hampstead Girls in my very early 20s, and had I known her then, I can imagine myself conceiving quite the tendresse for Kate of that sorority. Just look at her portrait by Red Saunders, the famous radical photographer, in the Eye Magazine’s issue 97. Don’t that crisp suit and those not-too-sensible shoes speak volumes? Isn’t this the very image of someone at ease with herself and her role in many worlds?

True to her being a Hampstead woman, but no stereotype, she was a close and collaborative friend of Dorothy Bohm (1924-2023), her near neighbour and a notably dapper émigré photographer who informally chronicled both Hampstead and Sussex, and half the world.

Leave a comment