SKN and Lucie Rie

Excellent and, as usual, tantalising evidence of Stanley North’s nature has quite suddenly been put my way. Tanya Harrod, the writer on the history and relationship of the worlds of art and of crafts, wrote asking me for some information about Stanley. Along the way Dr Harrod told me that Lucie Rie, the crucial modernist potter, had formed a strong relationship with Stanley, shortly after her arrival in London and late in his quite short life.

In no time I was able to read about their friendship in Tony Birks’ biography of LR. 1Footnote: Tony Birks, Lucie Rie, (1st edition 1987, others since), revised edition, 2009 It showed that SKN, visiting an archery club’s clubhouse in Albion Mews, Bayswater had, out of curiosity, wandered across the cobbles to investigate LR’s pottery studio (I imagine it being visible through open coach-house doors). They took to each other, and thenceforth spent a good deal of time together, with various creative co-operations.

They met, I deduce from Birks’s insightful but sometimes imprecise or inaccurate text, in 1939 (or possibly 1940) when she first set herself up in Albion Mews. Stanley bought the first pots she made in England. A little later, he returned them to her, saying their true home was in her studio, where indeed they stayed until she died in 1995. (Here’s a link to my sort-of timeline for SKN’s life and work.) 2Footnote: The SKN point here is that his being drawn to Lucie Rie’s work speaks both to his modernism and his being alert to the adventures in traditionalism which craft work represents. Her work may well also have chimed with the taste for a Korean and Japanese aesthetic which he may have shared. If, as his funeral suggests, he was also of a Buddhist frame of mind, such an aesthetic may well have sat well with him.

The RDN point, in case it’s of interest, is that sometime in Spring 2023 I became aware of Lucie Rie, her story and work. It may have been at the Shōji Hamada show at the Museum of Art and Craft, Ditchling where I seem to recall I bought a couple of sets of postcards of three of her pots. And then I was sorely tempted to schlepp over to Kettle’s Yard (Cambridge) or, later, the Holbourne gallery (Bath) for their ‘Lucie Rie: The Adventure of Pottery’ show, with its glorious poster and cover photo for the accompanying book, including an essay by Tanya Harrod, amongst others.

A further RDN/SKN point: I very much like the way Lucie Rie positively refused to discuss the ‘meaning’ of her work. I don’t know that SKN was deliberately reticent about anything. In his early 50s he was perhaps too busy giving his views on painting conservation, and supporting a revival in flax growing, the agricultural use of human sewage, and Alfred Munnings to take on wider aesthetic debate. But I know that he was smitten by Rie’s pots, and am thrilled that I became so just before I became aware of his interest in her work. I also know that I have over the past decade or so been drawn to make several pilgrimages to the oriental pots in the British Museum and to the ceramics at Stoner Park, near Henley. They feel like important components of an argument I am developing about whether the word ‘spiritual’ has any meaning in a material universe.

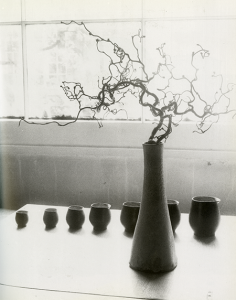

With something like eerie synchronicity on November 1st 2023 Phillips sold the ‘seven graduated pots’ for £44,450 and posted a decent colour picture of them on their website. (If you pursue the Phillips link, perhaps remember to keep scrolling until you are offered the link to the PDF of the full catalogue: it has the images and history.) Their cataloguing confirms the provenance trail from SKN’s purchase.

The Birks biography and the Phillips catalogue have a 1995 photograph of these ‘seven graduated pots’ in situ in the mews. It’s by Jane Coper, the wife of Hans Coper, Lucie Rie’s famous collaborator. Dr Harrod says the pots were photographed in the downstairs showroom. I cannot resist reproducing the photo, and if that becomes a copyright issue I hope someone will let me know. 3There is a colour photo of the ‘seven graduated pots’ and the cooling-tower’ vase, with other Rie pots, one of Bernard Leach’s, and a standing Lucie Rie, taken in the mews ground floor showroom. It’s in Tanya Harrod’s Real Thing: Essays on Making in the Modern World, Paperback, Hyphen Press, 2015. I don’t yet know the post-1995 history of the skinnified-cooling-tower vase which is also in the picture, nor the strength of any assumption that it is part of the SKN purchase. Doubtless that will become clear at some point.

The whole Lucie Rie episode, and perhaps most extraordinarily, his purchase and return of historically important LR works, and the way the events came to light (through someone’s reading posts here about SKN), seem like gifts from the ether. This Rie evidence is on a par with the way I was told about SKN’s 1915 manuscript for the Lord’s Supper, and his relationship with Helen Kennedy, as chronicled by Elsie Oxenham in her young-women novels of the 1920s.

When I have the most recent biography of Lucie Rie to hand (Emmanuel Cooper’s Lucie Rie from 2009) I will augment this short piece with whatever evidence I find there.

Meantime, here are some quotes from the Birks:

‘Lucie remembers feeling that from the moment he stepped into the studio he never really left.’

And ….

‘He [SKN] enlisted her help with his own projects, which involved ceramic tiles. He tried pottery, and he designed an “LR’ seal for her pots”. He just wanted to work with Lucie. How Bernard Leach took the arrival of this man on to the scene one can only guess, but certainly Lampl, Lucie’s other great supporter at the time, got on well with Stanley North and at the end of the working day Stanley would go from Albion Mews to accompany Fritz Lampl to Paddington Station through the darkened wartime streets. Since both of them suffered from night blindness, it would have been more useful if Lucie had gone instead.’

And …

[Lucie was in hospital in London, with an old medical problem. She] ‘stayed in for six weeks. While she was there, Stanley North, already ill with cancer, was also taken to hospital and the bright friendship which had so quickly grown between the two was to be extinguished. Three days after Lucie came out of hospital, Stanley North died of lung cancer. This man had become the most important person in Lucie’s life, and she went to his dignified but poorly attended Buddhist funeral while really ill herself. In wartime his own family could hardly reach England from South Africa. Lucie was ill and weak, and the Dartington idyll of 1939 with Leach and the happy early days in Albion Mews in 1940 [it is possible that that date should be 1939, or 1940] with Stanley North had turned swiftly, by 1941 [actually, until he died in 1942], into a time of deep sadness. Not since her brother Paul had died in 1917 had Lucie felt such a personal loss.’

And …

‘Of course Lucie’s circle of friends increased during the war, which brought people of all sorts together, but after the death of Stanley North she did not have a close English companion.’

Footnotes

- 1Footnote: Tony Birks, Lucie Rie, (1st edition 1987, others since), revised edition, 2009

- 2Footnote: The SKN point here is that his being drawn to Lucie Rie’s work speaks both to his modernism and his being alert to the adventures in traditionalism which craft work represents. Her work may well also have chimed with the taste for a Korean and Japanese aesthetic which he may have shared. If, as his funeral suggests, he was also of a Buddhist frame of mind, such an aesthetic may well have sat well with him.

The RDN point, in case it’s of interest, is that sometime in Spring 2023 I became aware of Lucie Rie, her story and work. It may have been at the Shōji Hamada show at the Museum of Art and Craft, Ditchling where I seem to recall I bought a couple of sets of postcards of three of her pots. And then I was sorely tempted to schlepp over to Kettle’s Yard (Cambridge) or, later, the Holbourne gallery (Bath) for their ‘Lucie Rie: The Adventure of Pottery’ show, with its glorious poster and cover photo for the accompanying book, including an essay by Tanya Harrod, amongst others.

A further RDN/SKN point: I very much like the way Lucie Rie positively refused to discuss the ‘meaning’ of her work. I don’t know that SKN was deliberately reticent about anything. In his early 50s he was perhaps too busy giving his views on painting conservation, and supporting a revival in flax growing, the agricultural use of human sewage, and Alfred Munnings to take on wider aesthetic debate. But I know that he was smitten by Rie’s pots, and am thrilled that I became so just before I became aware of his interest in her work. I also know that I have over the past decade or so been drawn to make several pilgrimages to the oriental pots in the British Museum and to the ceramics at Stoner Park, near Henley. They feel like important components of an argument I am developing about whether the word ‘spiritual’ has any meaning in a material universe. - 3There is a colour photo of the ‘seven graduated pots’ and the cooling-tower’ vase, with other Rie pots, one of Bernard Leach’s, and a standing Lucie Rie, taken in the mews ground floor showroom. It’s in Tanya Harrod’s Real Thing: Essays on Making in the Modern World, Paperback, Hyphen Press, 2015.

Footnotes

- 1Footnote: Tony Birks, Lucie Rie, (1st edition 1987, others since), revised edition, 2009

- 2Footnote: The SKN point here is that his being drawn to Lucie Rie’s work speaks both to his modernism and his being alert to the adventures in traditionalism which craft work represents. Her work may well also have chimed with the taste for a Korean and Japanese aesthetic which he may have shared. If, as his funeral suggests, he was also of a Buddhist frame of mind, such an aesthetic may well have sat well with him.

The RDN point, in case it’s of interest, is that sometime in Spring 2023 I became aware of Lucie Rie, her story and work. It may have been at the Shōji Hamada show at the Museum of Art and Craft, Ditchling where I seem to recall I bought a couple of sets of postcards of three of her pots. And then I was sorely tempted to schlepp over to Kettle’s Yard (Cambridge) or, later, the Holbourne gallery (Bath) for their ‘Lucie Rie: The Adventure of Pottery’ show, with its glorious poster and cover photo for the accompanying book, including an essay by Tanya Harrod, amongst others.

A further RDN/SKN point: I very much like the way Lucie Rie positively refused to discuss the ‘meaning’ of her work. I don’t know that SKN was deliberately reticent about anything. In his early 50s he was perhaps too busy giving his views on painting conservation, and supporting a revival in flax growing, the agricultural use of human sewage, and Alfred Munnings to take on wider aesthetic debate. But I know that he was smitten by Rie’s pots, and am thrilled that I became so just before I became aware of his interest in her work. I also know that I have over the past decade or so been drawn to make several pilgrimages to the oriental pots in the British Museum and to the ceramics at Stoner Park, near Henley. They feel like important components of an argument I am developing about whether the word ‘spiritual’ has any meaning in a material universe. - 3There is a colour photo of the ‘seven graduated pots’ and the cooling-tower’ vase, with other Rie pots, one of Bernard Leach’s, and a standing Lucie Rie, taken in the mews ground floor showroom. It’s in Tanya Harrod’s Real Thing: Essays on Making in the Modern World, Paperback, Hyphen Press, 2015.

Leave a comment