Discovering “The Lord’s Supper”

Stanley North was aged 28 when he made an imagined medieval manuscript of part of the Book of Common Prayer, “The Lord’s Supper”, the Communion service, in 1915. Its 150-odd pages became famous, in a circuitous way, when another of his illustrated manuscripts was given honourable mention in a famous series of “Girls’ Books” by Elsie J Oxenham. More below the fold, as one might say in the world of newsprint.

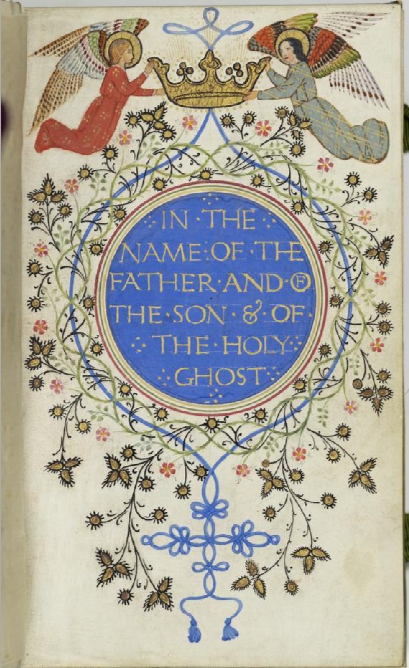

Stanley North, “Order of the Administration of the Lord’s Supper or Holy Communion”, 1915

The above title is also a link to a PDF which will usually open in a new tab and is downloadable.

The illuminated manuscript is archived in the USA, here:

The Pitts Theology Library, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia

Stanley’s manuscript transcribes part of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP), or Common Prayer. It seems to follow the version ordained by Elizabeth I’s parliament in 1571 and aimed at settling the rows following the Reformation and her father Henry VIII’s establishment of the Church of England. That’s the version of Common Prayer (published by Eyre and Spottiswood for the SPCK) which was around in 1913. But that may not be the exact version of the BCP which Stanley worked from: there were several revisions, especially one in 1662.

(See Wikipedia on the Thirty-nine Articles.)

I have no clue as to the life of Stanley’s “Lord’s Supper” except that it found its present home when the Pitts Theology Library bought it on 3 October 1989 from the bookseller Brian Carter whose address was 18D Newlun Hall Street, Oxford, OX1 2DW. Brian Carter was a regular supplier to the library.

The Abbey Girls, Stanley’s manuscript and Helen Kennedy North

Knowledge of Stanley’s “The Lord’s Supper” (1915) came to me from Clare Pascoe, an Australian fan of the “Abbey Girls” series of books (1914-1959) by Elsie J Oxenham (1880-1960). Much of what she told me, and the trail to Stanley’s artwork, was a revelation to me.

At least a couple of the books refer to Stanley including The Abbey Girls Go Back to School (1922) but especially, The New Abbey Girls (1923).

Free download: https://www.fadedpage.com/showbook.php?pid=20210319

NB: This is a legal server, operating under Canadian copyright rules.

The New Abbey Girls appeared in the period from 1920 when Stanley North married his second wife, Helen Kennedy, a big figure in the English Folk Dance & Song Society (EFDSS). The couple became Helen Kennedy North and Stanley Kennedy North, itself a progressive move. Their names do not appear in the Abbey Girls stories, though at least one of the series was dedicated to Helen Kennedy North. HKN appears in the series fictionalised simply as “Madam” and SKN simply as “Husband” (definitely hers). He is characterised as producing illustrated manuscripts as a work of love and craftsmanship, in the monastic tradition. Stanley was in real life a dedicated fan of EFDSS work, playing the Northumbrian “small pipes”, illustrating a book of songs dedicated to Cecil Sharp, the movement’s leader, and dancing very vigorously, the last characteristic appearing in The New Abbey Girls. The couple is also depicted in TNAG as creating a unique décor for their West End London flat (in line with SKN’s known craftsmanship in furniture-making).

At some point recently, Clare pursued the link from the known Helen Kennedy North, as “Madam”, to her known husband Stanley Kennedy North (“Husband”). She then searched “Stanley North + manuscript” online and got to the 1915 manuscript in one or two clicks. It had never occurred to me to make such a search. On every count I am very grateful for this new information and not least about the novels which I didn’t know at all and have only lightly index-hopped even now.

Actually, though, Stanley did the “Lord’s Supper” manuscript several years before the work referred to in The New Abbey Girls. It is true, though, that early in his marriage to Helen, Stanley did produce the sort of manuscript referred to in The New Abbey Girls, namely an iteration of the medieval “French love poem”of the story: it is “Aucassin and Nicolette”, which was enjoying a vogue at the time. Coincidentally, Clifford Bax also did a retelling of the French story (though I don’t think that is the text SKN followed in his illustrated manuscript). I don’t know how Stanley and Clifford’s life became intertwined. But I do know that Stanley also comes to life in another work of fiction: Clifford Bax’s novel, Many A Green Isle (1927) depicting the artist’s first marriage, to Vera Rawnsley.

The Abbey Girl novels were about a group of youngsters in a boarding school and their life afterwards as young adults. We meet Cicely whose story imparts special meaning to her co-founding The Hamlet Club. There is also an important element of what we now call “positive thinking” and the club’s motto was, “To be or not to be”. It emphasises the importance of making a right choice (the self-sacrificial one) when confronted with a dilemma. But it has elements of do-or-die, as well. Its ethos is also redolent of the Campfire movement for girls, which the Oxenham family espoused. (I rather doubt that Stanley was all that good at ardent joining-in.) The fictional school was near a ruined abbey, based on Cleeve Abbey, Somerset, a Cistercian monastery until Henry VIII’s Dissolution. The idea of monastic life, including the monks’ production of illustrated manuscripts, exerts considerable influence over some of the group. As schoolgirls we see the Abbey Girls navigating peer-group pressure and snobberies which are familiar today. They go on rambles (including to the Abbey) and do country dancing to folk tunes. As thrusting young women in the post-war 1920s the group become Arts & Crafts modernists and proto-feminists, whilst nurturing careers and – some of them – finding husbands, whilst others prefer the sororiety. As the plot thickens across the series, the Abbey becomes even more important to them.

I have never seen any evidence that Stanley was religious. So I have no inkling why he undertook the considerable task of transcribing great swathes of the Common Prayer Book. It may be explained by the apparent dedication page of “The Lord’s Supper”: “GN to M [&] EN”. I have no idea what it means. “GN” bears no obvious relation to Stanley North, SN, as he was then. I can’t see any connection in what I know of SN’s life at that time to an “M” and “EN”. It is possible that SN was sponsored to do this work by a GN, and that it is GN’s connections that would give us M and EN. The clue may lie in Stanley’s relationship with the young Margaret Gardiner (in whose memoir he appears as a strong influence, affectionately remembered). But Stanley had a wide acquaintance and presumably many possible patrons. Anyway, Margaret’s account is that she couldn’t remember when she first met Stanley, except that it “must have been quite early in the war” (WW1).

It is interesting that across the 1914-1951 period of the series, not only did the fictional group of girls grow up but so did the readers who had been with them for decades. Presumably, too, the readership was augmented by a wide age-range of (mostly) female readers.

.

14/03/23